Lessons from Tutoring – a start, at least

I have the weirdest job in the world. That’s definitely overstating it, but its the kind of thing that situates itself between salesperson (a job of infinite reproducibility) and a rockstar (a job of unique specificity), where I’m the thing I’m selling with limited infrastructure surrounding me. I feel sometimes like a weed guy, sort of off the grid, getting people their hookup, and like a con artist who cynically doubts the effective value of their work. I’m a tutor. I know no one like me. I have no collaborators, I have no coworkers. On a daily basis I am engaged in growing young minds, and on a daily basis I learn from my students, I learn from myself, I learn from what happens when we are working together, I learn from parental and educational systems that encase my students, I learn and learn and learn. I have a lot to say, but I do not know the order in which it will come out. So this is a beginning, a start, at least, at unraveling those lessons.

This is also a declaration to all parents, a desperate plea for ears, and it stems from a recurring frustration at breaking the cycles of control that work to traumatize and manipulate all of us, but that start in our homes and schools. We can unwork this damage, we can heal, we can move forward, we can change our educational system into something that aspires to a greater purpose than producing the future working class and elite, we can make changes. It is never too late. We can unwork the problems I want to describe in every interaction we have in a day, because they affect all of us, they were the first spaces in which came into an understanding of our worth – many of us may already be doing this in some way. But it starts with us, we are responsible for our own healing.

Our education system, our whole cultural mentality around education is toxic, broken, traumatizing, and obsolete to boot – a cultural artifact of the industrial revolution. I intend to write out things I’ve observed in my students over the last six years. I have worked with hundreds of students from different backgrounds and with different abilities and desires, though largely from families with a good degree of privilege, and every session is an experimental space in which I test pedagogic techniques I’ve been honing, and try out new ones, and learn from the results of my experiments. What I have to say here and in future posts is a consequence of conclusions I’ve drawn about the evidence I’ve noticed in my work. It’s also based on my experiences teaching in classrooms at multiple community colleges, and teaching at a high school in a teacher-tutor hybrid role. This can all be taken as my analysis of my experiments, not meant to relate to any other writing on the subject, nor meant to prove a thesis of some kind, these are observations and beliefs about what those observations mean, most likely flawed in their conception in some way throughout, but I can tell that few have the vantage point I have, and it seems worth writing about for that reason alone. So this will be the first of likely several (3-4) posts worth of lessons from tutoring.

So I tutor primarily high school and college students to prepare them for standardized tests. This would be my area of expertise, perhaps now above all things except cinema (and even there, it gives it a run for its money). I’ve worked with students on the ACT, SAT, GRE, GMAT and some of their minor forms (in addition to more generalized help on specific subjects). I assist sometimes with the application process as a whole, helping students plan and edit their essays for admission, their resumes, their search for colleges in the first place.

I had a parent ask me recently – “What’s your opinion: should we sign the student up for an extra test in December? I was talking to other parent and they were talking about how the seniors don’t take it then because its too late, so it’ll be a less packed place to take the test, and that could be helpful, right? Every little bit counts!” There’s a lot in here that is harmful and widespread. Let’s talk about a few things.

Lesson #1: The test is never a neutral space for a child. The test determines their value, it places a number on it, and that number is designed to place them relative to their peers in a relationship of better vs worse. This is instilled in us from such a young age that my framing it in this way will feel radical to most people, because they have internalized the mechanism of the test themselves, or view it as a natural/necessary part of the world’s functioning. In what way could you imagine an education that isn’t dependent on viewing yourself or your friend as “worse”?

Lesson #2: Does a test evaluate knowledge? Not especially, I would argue. There are more effective ways to evaluate knowledge, because there are lots of different kinds of knowledge. Some kids know how to do a thing while they are doing it with their body, but can’t find the words to explain it. In most cases, however, I find the question is one of access to knowledge, not possession of knowledge. Most of my students are extremely anxious kiddos. I’ve worked with them on material when they are in a calmer state and the information they seek comes readily. When they feel they are being judged or evaluated (precisely the phenomenon of the test), their anxiety shoots up and they blank and can’t remember a thing. I would say most teachers know there are other ways of evaluating students, as they have plenty of kids who don’t seem to do well on tests but are great in class. In truth, I’d say we need a multiplicity of ways to do this and work to give students more consent over their education.

Lesson #3: We need to try to keep the test, and the expressions of value from the school, from entering the home. Urgently. Listen to your kids, folks. Take their side. The school isn’t evil in some sociopathic way, but it is an institution of control whose evil is in its banality. We cannot be taking what is said there for granted. Teachers may act of their own accord relative to engagements with a parent, so teachers are worth trusting, but most people at a school are just not invested in your kid the way you are.

Something that was specifically frustrating in the example I’m expounding upon was the sense that “every little bit counts” – this is a most harmful expression. It’s not based in any reality, but spurs action and does so blindly. This parent was concerned with getting their student from a 29 to maybe a 30 or 31 or 32 on the ACT. This is of course the goal of any attempt at retaking the test, increasing the score. But this expresses in the home, from the parental models, the idea that the student’s performance was not good enough. In my sessions, regardless of how many questions are answered or missed, I always remind the students that they’ve done good work for the day, because they have. They’ve done mental gymnastics, they’ve tried to solve puzzles. Taking tests is hard work. Getting any score above a certain amount is a reason to celebrate, not cause to consider if they should run an extra marathon. It also reproduces the work of the test – which is compressed valuation – and normalizes its description. The test measures the test, this is all folks. We gotta stop repeating its truth at home, and that might go for grades too.

Lesson #4: As hinted at above – the test is a physical endeavor. The brain is a muscle, and we feel physically exhausted after doing lots of thinking. People do not need to spend all of their waking days in preparation for a marathon that they did not choose to run. But this is the regime of test prep, and it is widespread practice at this point for parents to have their students take these marathon tests up to 5 times. For the parent, the work done is clicking yes, and signing a check, and believing they’ve done the right thing for their child. It’s an endorphin rush, its the same kind of thing we get when we click Buy Now on Amazon or Like on Facebook… we register our kids for college and these tests through a deeply marketed space of competing advertisers, but we don’t see them that way because of the normalization of it all. The child, though, has to sit down and take the test approximately five times in practice for every time they take it in reality.

Taking the test is no small matter – it structures our sense of self worth while exhausting us and demanding we display our knowledge in a very contorted specific way (that doesn’t even resemble how we might deploy it in the real world).

My sense is that psychologically this is true across the board – the test I’m referring to here is all tests, though it is worse among standardized tests. Preparing for them is a closed loop, one learns skills for taking the test that are irrelevant elsewhere.

Lesson #5: Parents’ worst enemy is each other, the community of parents that they mark as their parental community. Oftentimes this is connected through the school – these are the relationships that are least well grounded, as they are expressed primarily through the scholastic relationship between the students, and so they carry forward in their dynamics the measuring that the school imposes on the two students, making the parents at least potentially competitive in ways that are harmful to their kids. This competitiveness can be of the form that they take the same side, and are both gonna make sure their kids get into top colleges (unlike the other kids), or it can make them competitive against each other, which is more transparently petty.

I have had to argue with as many parents not in the room as parents in the room about whats best for their child – too many will try to do something harmful, or pressure their kid into bad scenarios because they’ve heard from another parent about what “works.”

Lesson #6: “What Works” or “The Answer” — These are problematic constructions sometimes. When we typically talk about finding what works, its usually from a thing we’ve done a bunch, like cooking a steak or making rice, or putting up wallpaper – we know what works from trial and error. Boy oh boy does that meaning dissipate when it comes to future/college/education based anxieties for folks. They often seek a solution that works without being engaged in producing it, so they borrow the solutions of their neighbors in the hopes that it will work for them, when this is futile at it’s core. This is based, I believe, out of an inherited sense of the value of specific answers to questions. We need to have The Answer, because if we don’t have The Answer to a Question, then we become Wrong. The way I’m writing is a kind of parody of Freud, but I see it as a kind of primal scene for one of our own relationships to our minds. We experience the trauma of being marked as wrong over and over again, each test tells us all of the ways in which we are wrong. If we can internalize that, what it shifts in us is a desire for the right answer over the right pathway. If you hit a child for lying they don’t stop lying, they become better liars. We are all of us the children hit by wrong answers, and eventually we learned how to pretend we knew things, instead of working through them for ourselves. This is maybe the hidden goal of our broken system: it desires to produce individuals who know without thinking, who have so many answers they never start asking questions, because they can point at the answers and call it knowledge. Increasingly, what we refer to when we refer to “what works” isn’t based on our own experience or the experiences of people around us, but our fears, and the fears of those around us, masquerading as answers.

This deserves more unpacking in future posts, but these are the lessons for today.

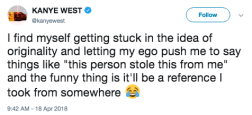

The source for most folks is from Jim Jarmusch’s

The source for most folks is from Jim Jarmusch’s  fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows.

fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is nonexistent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery—

Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is nonexistent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery—

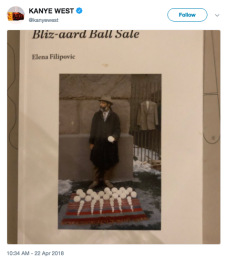

“One wintry day in 1983, David Hammons peddled snowballs of various sizes. He laid them out in graduated rows and spent the day acting as an obliging salesman. Calling the unannounced street action Bliz-aard Ball Sale, he inscribed it into a body of work that, from the late 1960s to the present, has used a lexicon of discreet actions and consciously ‘black’ materials to comment on the nature of the artwork, the art world, and race in America.”

“One wintry day in 1983, David Hammons peddled snowballs of various sizes. He laid them out in graduated rows and spent the day acting as an obliging salesman. Calling the unannounced street action Bliz-aard Ball Sale, he inscribed it into a body of work that, from the late 1960s to the present, has used a lexicon of discreet actions and consciously ‘black’ materials to comment on the nature of the artwork, the art world, and race in America.”

basketball hoops, meticulously decorated with bottle caps, evoking Islamic mosaic and design; and Higher Goals (1986), where an ordinary basketball hoop, net, and backboard are set on a three-story high pole – commenting on the almost impossible aspirations of sports stardom as a way out of the ghetto.”

basketball hoops, meticulously decorated with bottle caps, evoking Islamic mosaic and design; and Higher Goals (1986), where an ordinary basketball hoop, net, and backboard are set on a three-story high pole – commenting on the almost impossible aspirations of sports stardom as a way out of the ghetto.”

One of his most famous pieces is “I Like America and America Likes Me.” It would seem that this piece in particular, perhaps more than any other so far, is indispensable in making sense of this release. You can read the full account

One of his most famous pieces is “I Like America and America Likes Me.” It would seem that this piece in particular, perhaps more than any other so far, is indispensable in making sense of this release. You can read the full account  “You could say that a reckoning has to be made with the coyote, and only then can this trauma be lifted,” he said of his performance. For those three days, he attempted to make eye contact with the coyote while regularly performing symbolic gestures, such as tossing his leather gloves to it or gesticulating wildly at it with his hands and walking stick.” At the end of the performance, Beuys embraced the coyote, and the coyote allowed this.

“You could say that a reckoning has to be made with the coyote, and only then can this trauma be lifted,” he said of his performance. For those three days, he attempted to make eye contact with the coyote while regularly performing symbolic gestures, such as tossing his leather gloves to it or gesticulating wildly at it with his hands and walking stick.” At the end of the performance, Beuys embraced the coyote, and the coyote allowed this. In the above tweet (also featured at the top of this post), Kanye has sketched a caricature of someone’s face next to the name Andy. This Andy could signify in multiple directions (Kanye has done this previously with BIG Pun/L/Notorious, Russell Simmons/Crowe/Brand/Naomi, Michael Jackson/Jordan/Tyson/Phelps, and Pablo Picasso/Escobar/the Apostle), but it seems most likely to be a representation of Andy Kaufman, postmodern comic/prankster of the 70s and 80s. He notably performed duplicitously, often in character or as someone else in ways that seemed to be awkward, uncomfortable, or disorienting. He took the social sphere as his medium as a comic, famously getting into a public feud with a wrestler and getting decked on live TV.

In the above tweet (also featured at the top of this post), Kanye has sketched a caricature of someone’s face next to the name Andy. This Andy could signify in multiple directions (Kanye has done this previously with BIG Pun/L/Notorious, Russell Simmons/Crowe/Brand/Naomi, Michael Jackson/Jordan/Tyson/Phelps, and Pablo Picasso/Escobar/the Apostle), but it seems most likely to be a representation of Andy Kaufman, postmodern comic/prankster of the 70s and 80s. He notably performed duplicitously, often in character or as someone else in ways that seemed to be awkward, uncomfortable, or disorienting. He took the social sphere as his medium as a comic, famously getting into a public feud with a wrestler and getting decked on live TV. In his interview with Axel Vervoordt, Kanye announced his plans to write a book called Break the Simulation, something he proceeded to publish live on Twitter for the foreseeable future. It seems to revolve around the theory that the real world has been supplanted by an illusion, like photographs that we get lost in, and a sense of being programmed to perceive the world in a particular way. He’ll continue to elucidate this over time, but it’s clear he’s referencing the work of French postmodern philosopher Jean Baudrillard, who wrote Simulacra and Simulation in the 70s. His argument is very theoretical and depends upon theories of “signs” and “signifiers” but he predicts a kind of apocalypse of Sense bound up in the disconnection between symbols and their referents. He charts out a proposed future of “that which signifies” and argues that we will soon reach a point where the image/sign refers to nothing but itself (this, after all, is one of our colloquial definitions of celebrity especially in relation to the Kardashians – famous for being famous). Think of drivers who don’t look at the road in front of them, or think about the city they navigate, but depend on mapping/direction apps to find their way. A digital road, and a digital city have replaced the “real”.

In his interview with Axel Vervoordt, Kanye announced his plans to write a book called Break the Simulation, something he proceeded to publish live on Twitter for the foreseeable future. It seems to revolve around the theory that the real world has been supplanted by an illusion, like photographs that we get lost in, and a sense of being programmed to perceive the world in a particular way. He’ll continue to elucidate this over time, but it’s clear he’s referencing the work of French postmodern philosopher Jean Baudrillard, who wrote Simulacra and Simulation in the 70s. His argument is very theoretical and depends upon theories of “signs” and “signifiers” but he predicts a kind of apocalypse of Sense bound up in the disconnection between symbols and their referents. He charts out a proposed future of “that which signifies” and argues that we will soon reach a point where the image/sign refers to nothing but itself (this, after all, is one of our colloquial definitions of celebrity especially in relation to the Kardashians – famous for being famous). Think of drivers who don’t look at the road in front of them, or think about the city they navigate, but depend on mapping/direction apps to find their way. A digital road, and a digital city have replaced the “real”. Throughout his career, David Bowie changed personas and styles every couple of years – a dynamism shared by Kanye’s own career. The Thin White Duke was the character he adopted from 1975 to 76, largely following the end of his Young Americans album, and predominantly associated with Station to Station, modeled partially after the character he played in Nic Roeg’s Man Who Fell to Earth. From Wikipedia: “The Thin White Duke was a controversial figure. While being interviewed in the persona in 1975 and 1976, Bowie made statements about Adolf Hitler and fascism that some interpreted as being positive or even pro-fascist.The controversy deepened in May 1976 when, while acknowledging a group of fans outside ofLondon Victoria station, he was photographed making what some alleged to be a Nazi salute. Bowie denied this, saying that he was simply waving and the photographer captured his image mid-wave. As early as 1976, Bowie began disavowing his allegedly pro-Fascist comments and said that he was misunderstood. In an interview , he explained that while performing in his various characters, “I’m Pierrot. I’m Everyman. What I’m doing is theatre, and only theatre… What you see on stage isn’t sinister. It’s pure clown. I’m using myself as a canvas and trying to paint the truth of our time on it. The white face, the baggy pants – they’re Pierrot, the eternal clown putting over the great sadness.” In 1977 (after retiring the Duke), Bowie stated that “I have made my two or three glib, theatrical observations on English society and the only thing I can now counter with is to state that I am NOT a Fascist”.

Throughout his career, David Bowie changed personas and styles every couple of years – a dynamism shared by Kanye’s own career. The Thin White Duke was the character he adopted from 1975 to 76, largely following the end of his Young Americans album, and predominantly associated with Station to Station, modeled partially after the character he played in Nic Roeg’s Man Who Fell to Earth. From Wikipedia: “The Thin White Duke was a controversial figure. While being interviewed in the persona in 1975 and 1976, Bowie made statements about Adolf Hitler and fascism that some interpreted as being positive or even pro-fascist.The controversy deepened in May 1976 when, while acknowledging a group of fans outside ofLondon Victoria station, he was photographed making what some alleged to be a Nazi salute. Bowie denied this, saying that he was simply waving and the photographer captured his image mid-wave. As early as 1976, Bowie began disavowing his allegedly pro-Fascist comments and said that he was misunderstood. In an interview , he explained that while performing in his various characters, “I’m Pierrot. I’m Everyman. What I’m doing is theatre, and only theatre… What you see on stage isn’t sinister. It’s pure clown. I’m using myself as a canvas and trying to paint the truth of our time on it. The white face, the baggy pants – they’re Pierrot, the eternal clown putting over the great sadness.” In 1977 (after retiring the Duke), Bowie stated that “I have made my two or three glib, theatrical observations on English society and the only thing I can now counter with is to state that I am NOT a Fascist”. It’s entirely possible that Bruce Lee hold the secret to the “Dragon Energy” that Kanye and Trump apparently share, but in any event it is clear that Kanye is engaging with Bruce Lee’s personal philosophy and especially the film Enter the Dragon. Lee writes and speaks a lot about how important feeling is, as opposed to thinking, how to organize your body and senses towards the pursuit of victory. He opposes the concept of enemies, and concludes that the primary battle is always with the self. These are consistent with some of Kanye’s latest maxims. He also spoke about his identity as a person associated with multiple nationalities. In the third clip below, Lee is asked whether he views himself as a Chinese man or a North American man, and he responds by saying he’s a human being. This has been an element of Kanye’s recent philosophy as well (at TMZ he spoke briefly about how important it was to develop a language that felt it could apply to all, because “we aren’t white and black, we’re all one race, the human race” – which sounds goofily post-racial, but here is almost perfectly a quote from Lee).

It’s entirely possible that Bruce Lee hold the secret to the “Dragon Energy” that Kanye and Trump apparently share, but in any event it is clear that Kanye is engaging with Bruce Lee’s personal philosophy and especially the film Enter the Dragon. Lee writes and speaks a lot about how important feeling is, as opposed to thinking, how to organize your body and senses towards the pursuit of victory. He opposes the concept of enemies, and concludes that the primary battle is always with the self. These are consistent with some of Kanye’s latest maxims. He also spoke about his identity as a person associated with multiple nationalities. In the third clip below, Lee is asked whether he views himself as a Chinese man or a North American man, and he responds by saying he’s a human being. This has been an element of Kanye’s recent philosophy as well (at TMZ he spoke briefly about how important it was to develop a language that felt it could apply to all, because “we aren’t white and black, we’re all one race, the human race” – which sounds goofily post-racial, but here is almost perfectly a quote from Lee).

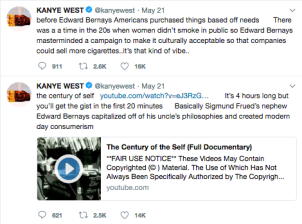

Kanye surprised the film world by posting a 4-hour long documentary by the esoteric political filmmaker Adam Curtis, titled The Century of the Self. While it might be easy to be distracted by his claim that the main point is made in the first 20 minutes, the fact that this was posted at all is remarkable. Curtis has been making incisive documentaries examining culture, politics, media, and power with the BBC for several decades now, though his work is under-appreciated. His most recent film, HyperNormalisation is an analysis of what might be called a politics of deception through media, or a history of terrorism, that culminates with the election of Trump in 2016. It was one of the most groundbreaking documentaries of the last couple years and is available, like most of his work, for free on YouTube.

Kanye surprised the film world by posting a 4-hour long documentary by the esoteric political filmmaker Adam Curtis, titled The Century of the Self. While it might be easy to be distracted by his claim that the main point is made in the first 20 minutes, the fact that this was posted at all is remarkable. Curtis has been making incisive documentaries examining culture, politics, media, and power with the BBC for several decades now, though his work is under-appreciated. His most recent film, HyperNormalisation is an analysis of what might be called a politics of deception through media, or a history of terrorism, that culminates with the election of Trump in 2016. It was one of the most groundbreaking documentaries of the last couple years and is available, like most of his work, for free on YouTube. These two luxurious resorts, apparently costing up to $10k a night, are the primary locations where the recording and producing of this summer’s albums occurred. They vibe greatly with the interests Kanye has expressed in relation to architecture, with an emphasis on natural proportions, and his framework for describing the luxurious (“one of one”).

These two luxurious resorts, apparently costing up to $10k a night, are the primary locations where the recording and producing of this summer’s albums occurred. They vibe greatly with the interests Kanye has expressed in relation to architecture, with an emphasis on natural proportions, and his framework for describing the luxurious (“one of one”). Both resorts are designed to exist in the location they are built in, using materials sourced nearby, and with an ethos of natural harmony.

Both resorts are designed to exist in the location they are built in, using materials sourced nearby, and with an ethos of natural harmony.  The woman who ushered in Yeezy Season 2018, Candace Owens, is a spokesperson for the political organization Turning Point USA. She’s famous in many respects for repeating many of the same talking points as other pop conservatives, like Tomi Lahren, emphasizing the importance of personal empowerment as a salvo to the effects of racism. This is a generous way of putting it. Many of Owens’ arguments feel out of touch with the weight of history, maintaining a disdainful and contemptuous view of the power of social movements, and she speaks at great length about how protestors and political activists engaged in struggle against a system that oppresses them are in fact falling right into it’s trap, that their political energy is being sapped and used by others who would also wish to control them. Famously, she talks of how black folks voting Democrat is a sign that they are still “on the plantation.”

The woman who ushered in Yeezy Season 2018, Candace Owens, is a spokesperson for the political organization Turning Point USA. She’s famous in many respects for repeating many of the same talking points as other pop conservatives, like Tomi Lahren, emphasizing the importance of personal empowerment as a salvo to the effects of racism. This is a generous way of putting it. Many of Owens’ arguments feel out of touch with the weight of history, maintaining a disdainful and contemptuous view of the power of social movements, and she speaks at great length about how protestors and political activists engaged in struggle against a system that oppresses them are in fact falling right into it’s trap, that their political energy is being sapped and used by others who would also wish to control them. Famously, she talks of how black folks voting Democrat is a sign that they are still “on the plantation.” That said, Kanye said “I love the way Candace Owens thinks”, breaking the internet in the process, and it’s worth addressing what he might love about how she thinks. He gave some context in a tweet a week later, featuring a whiteboard that Candace had written some ideas on. The image purported to describe the formation of a mind, through multiple stages of development. First is family, then Education, then Culture & Media. It seems to suggest that this is how a person’s politics comes into being, or how ideology is formed. I mean this whole thing is honestly Althusserian, even if we want to say that Candace Owens doesn’t know what she’s talking about, this drawing is something that reflects other understandings of how our “political selves” are produced by hegemonic forces. Kanye proceeded to tweet several of Owens’ catchphrases about self-victimization and not being able to get past the past, meaning that at least he vibes with these specific ideas of hers – though I would caution that Kanye probably likes something about these ideas that Candace herself doesn’t mean. The next section will elaborate the dynamic that I think this relates to.

That said, Kanye said “I love the way Candace Owens thinks”, breaking the internet in the process, and it’s worth addressing what he might love about how she thinks. He gave some context in a tweet a week later, featuring a whiteboard that Candace had written some ideas on. The image purported to describe the formation of a mind, through multiple stages of development. First is family, then Education, then Culture & Media. It seems to suggest that this is how a person’s politics comes into being, or how ideology is formed. I mean this whole thing is honestly Althusserian, even if we want to say that Candace Owens doesn’t know what she’s talking about, this drawing is something that reflects other understandings of how our “political selves” are produced by hegemonic forces. Kanye proceeded to tweet several of Owens’ catchphrases about self-victimization and not being able to get past the past, meaning that at least he vibes with these specific ideas of hers – though I would caution that Kanye probably likes something about these ideas that Candace herself doesn’t mean. The next section will elaborate the dynamic that I think this relates to. Amma Mata is revered as a saint and guru, known, as Kanye points out, for giving a great number of hugs to people. She also wrote and spoke extensively about the possibility of “liberation while alive”: “Jivanmukti is not something to be attained after death, nor is it to be experienced or bestowed upon you in another world. It is a state of perfect awareness and equanimity, which can be experienced here and now in this world, while living in the body. Having come to experience the highest truth of oneness with the Self, such blessed souls do not have to be born again. They merge with the infinite.” This sense that we can transcend our prisons in life seems useful to Kanye, in his recent framings of “mental slavery”, “mental prisons”, and his goal of Breaking the Simulation.

Amma Mata is revered as a saint and guru, known, as Kanye points out, for giving a great number of hugs to people. She also wrote and spoke extensively about the possibility of “liberation while alive”: “Jivanmukti is not something to be attained after death, nor is it to be experienced or bestowed upon you in another world. It is a state of perfect awareness and equanimity, which can be experienced here and now in this world, while living in the body. Having come to experience the highest truth of oneness with the Self, such blessed souls do not have to be born again. They merge with the infinite.” This sense that we can transcend our prisons in life seems useful to Kanye, in his recent framings of “mental slavery”, “mental prisons”, and his goal of Breaking the Simulation. The first time I met Burrel Farnsley, he was in a frumpy suit, partly shaven, toting around a box full of science posters on UofL’s campus. I was on my way to the Honors Building for quiz bowl practice, held there on the second floor on Wednesday nights most semesters. I’m the kind of guy that really is terrible at worming his way out of conversations, so I’ll usually humor a person, even if I’ve got somewhere to be, far longer than I really should.

The first time I met Burrel Farnsley, he was in a frumpy suit, partly shaven, toting around a box full of science posters on UofL’s campus. I was on my way to the Honors Building for quiz bowl practice, held there on the second floor on Wednesday nights most semesters. I’m the kind of guy that really is terrible at worming his way out of conversations, so I’ll usually humor a person, even if I’ve got somewhere to be, far longer than I really should. Jude Swanberg, son to filmmakers Joe and Kris Swanberg, has been stealing scenes throughout his infancy. To date, Jude has appeared in 8 films, in roles of varying capacity, but it’s been clear for some time that we are witnessing his earliest years through the cinema of his parents. It seems likely that this will decrease as he ages – babies are much cuter to photograph, and have less bodily autonomy with which they can resist their exploitation. However, the intersection between his real world identity and his on-screen

Jude Swanberg, son to filmmakers Joe and Kris Swanberg, has been stealing scenes throughout his infancy. To date, Jude has appeared in 8 films, in roles of varying capacity, but it’s been clear for some time that we are witnessing his earliest years through the cinema of his parents. It seems likely that this will decrease as he ages – babies are much cuter to photograph, and have less bodily autonomy with which they can resist their exploitation. However, the intersection between his real world identity and his on-screen  development produces curious resonances, that at minimum deserve some contemplation.

development produces curious resonances, that at minimum deserve some contemplation. also motivated by a DIY tendency, a desire to produce films using cheap materials speaking truths that might only be worth showing to their closest friends and acquaintances. That’s the kind of intimacy these filmmakers sought, as if you were living in their own home with them.

also motivated by a DIY tendency, a desire to produce films using cheap materials speaking truths that might only be worth showing to their closest friends and acquaintances. That’s the kind of intimacy these filmmakers sought, as if you were living in their own home with them. dynamics, that his own family would come into play as a subject of his films. Much more ought to be explored along these lines, as Swanberg’s cinema has changed greatly since the release of his film Drinking Buddies, a few months before the birth of his child.

dynamics, that his own family would come into play as a subject of his films. Much more ought to be explored along these lines, as Swanberg’s cinema has changed greatly since the release of his film Drinking Buddies, a few months before the birth of his child. Swanberg). In each of these films, Jude is appropriately cast as himself, or some screen version of himself, named Jude.

Swanberg). In each of these films, Jude is appropriately cast as himself, or some screen version of himself, named Jude. Joe/Kris/Jude in real life, often with one or both portraying a parent. [In EB, HC, UK2, J,

Joe/Kris/Jude in real life, often with one or both portraying a parent. [In EB, HC, UK2, J,